So What Exactly is an R-flex Shaft Anyway?

If you are looking at a definitive answer to the title’s question, you may be sadly disappointed with the answer and for good reason. Absolutely no one in whole wide world can answer that question and I am here to tell you the real reason. So sit back and absorb some vital information if you truly want to understand golf shaft flex better.

What is an R-flex?

Our opening question could have easily been what is an L, A, S, or X-flex as it is a means of establishing a standard. For those of you who are unaware of the nomenclature, R stands for Regular and is designed for – well, you guessed it – the regular guy. It is simply the flex built into the shaft to complement the strength of what the average male golfer may produce to provide the right feel and consistent results.

Shaft manufacturers have their own internal method of determining flex and building that into the design of a raw, uncut shaft and then suggesting a systematic way of trimming the shaft based on the weights and lengths that club manufacturers produce their wares. Believe me, that is no easy task. The reason being is there are no standards in the industry for the last two parameters.

Don’t Resist Change

Clubmakers and golfers alike want things that are neatly organized. That is from one manufacture to another or shaft model to the next, if it says R-flex on the label it will be the same. Well for one, if that were the case then all shafts would play exactly the same and we wouldn’t have any product differentiation. I think all of us would agree that would not be a positive situation.

But clubmakers would like the shafts to fall with in a tight range. For instance, if the shaft’s deflection or frequency (two methods of measuring relative shaft flex) were between X and Y-amounts, then the shaft can be definitively characterized as an R-flex or whatever flex we are trying to determine. As of now that does not occur and that is why I want to go over the reasons this type of system does not work.

Shaft Weight

For many, many years steel shaft producers made shafts that were all the same weight. Today we refer to them as standard weight steel shafts. These are shafts such as Dynamic Gold as one example that weigh approximately 3.0g or more per inch for irons. I like to put the weight in those terms because not every raw, uncut shaft is produced at the same length. A classic illustration is the Apollo Shadow Lite which is 115g at 42” or under 3.0g per inch, hence the “Lite” in the name.

When you have shafts that are of similar weight per inch there is not a whole lot of manipulation that steel shaft makers can do that a graphite shaft manufacturer can as the materials are consistent (or homogeneous) throughout. One of those ways to create differentiation is the step pattern or geometry of the shaft which affects the flex distribution which we will talk about next. We will re-visit the importance of weight afterwards.

Stiffness Distribution

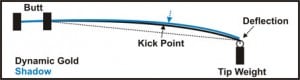

The flex distribution of a shaft, also known as bend point, kick point of flex point, is one way a manufacturer has in altering the feel and potentially the ball’s trajectory between different models. This is influenced by the distance between the steps or “knurls” on a steel shaft, parallel tip and butt lengths, outside diameters and wall thickness.

A shaft classified as a “low” bend point (a shaft designed to hit the ball high) has more of the flex built into the shaft more toward the tip section or where it is attached to the head. Conversely, a shaft classified as a “high” bend point (a shaft designed to hit the ball lower) has less of the flex built into the shaft’s tip section. A shaft classified as “mid” bend point has the stiffness distribution more evenly spread along the length of the shaft.

In order for a low bend point shaft to have more flex built into the tip means the shaft has a disproportionate amount of its stiffness in the butt end. In determining the flex of the shaft whether by deflection or frequency is done by clamping the butt end of the shaft and obtaining the measurements.

If you have two R-flex shafts of the same weight and length, the one with the lower bend point shaft will often appear to be stiffer even though it may not feel that way when swung. The original Apollo Shadow R-flex steel shaft is a prime example. The weight is the same as a Dynamic Gold which has the stiffer tip section. To offset this, the butt end is more flexible on the Dynamic Gold subsequently exhibiting a lower frequency or deflection reading. For that reason alone, there should be no absolute standards for the flex of a shaft.

If you have two R-flex shafts of the same weight and length, the one with the lower bend point shaft will often appear to be stiffer even though it may not feel that way when swung. The original Apollo Shadow R-flex steel shaft is a prime example. The weight is the same as a Dynamic Gold which has the stiffer tip section. To offset this, the butt end is more flexible on the Dynamic Gold subsequently exhibiting a lower frequency or deflection reading. For that reason alone, there should be no absolute standards for the flex of a shaft.

Emergence of Lighter Steel Shafts

Manufacturers have continued to produce lighter weight shafts as a means of lowering the overall weight of the club so it can be swung faster or with less effort so consumers could obtain more distance. In the early days of steel this was not possible. But as years went on, steel manufacturers figured out ways of reducing wall thickness and yet build durability into the shaft. The first generation of lighter weight shafts was a mere 7g lighter than their standard weight counterparts. Not exactly Earth shattering. Over the length of a 41” shaft, 7g amounts to 0.17g per inch.

Manufacturers built the flex of their new lighter weight shafts the same as the standard weight shafts. The formula worked for years until the next generation of even lighter weight shaft began. Those shafts weighing at least another 7g lighter than the lightweight steel shafts at the time again were created with the same flex. However, this time the thinner walled shafts began to feel “boardy” or unresponsive. The standard deflection and frequency readings that stood for years no long fit the formula.

Throwing a Curve Ball

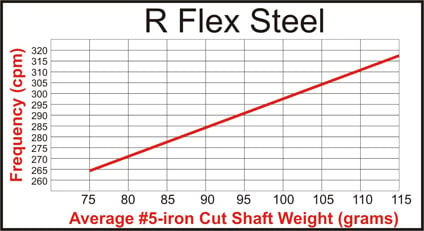

Soon afterward the steel manufacturers replaced those “boardy” feeling shafts with newer models that had more flex built into them. Manufacturers began doing blind testing with golfers to determine what feels and performs to the R-flex they were familiar with rather than using a secret formula. Clubmakers cried foul. These aren’t R-flex shafts they measure closer to senior (A-flex) shafts. Therefore the clubmaker or fitter would suggest S-flex shafts in the lighter weight pattern because the frequency and deflection reading matched that of the heavier weight R-flex shafts. After all, frequency is frequency and deflection is deflection at the same length – isn’t it? The chart listed shows plots typical assembled club frequencies of R-flex #5-irons at different cut shaft weights.

For years, graphite irons shafts were much more flexible than their steel counterparts – some 25 cycles per minute (cpm) lower in respect to the same flex steel-shafted #5-iron. It had always been accepted within the golf industry that 10 cpm was considered one full flex. At first club makers questioned why the great disparity but gradually over time began to accept it for various reasons such as different raw materials and assembly lengths. Plus the graphite shaft manufacturers didn’t deviate and start building back stiffness into their products to get them to have similar deflection and frequency reading as steel

For years, graphite irons shafts were much more flexible than their steel counterparts – some 25 cycles per minute (cpm) lower in respect to the same flex steel-shafted #5-iron. It had always been accepted within the golf industry that 10 cpm was considered one full flex. At first club makers questioned why the great disparity but gradually over time began to accept it for various reasons such as different raw materials and assembly lengths. Plus the graphite shaft manufacturers didn’t deviate and start building back stiffness into their products to get them to have similar deflection and frequency reading as steel

But now we have steel shafts like the Apollo Acculite 75 and True Temper’s GS-75 that are the weight of many graphite shafts. Their flex is also more proportional to graphite shafts of that weight too. Those that play these two shafts don’t find the playing flex to be characteristic of the lower frequency reading that would indicate the shafts are too weak.

What exactly is an R-flex shaft now?

Simply the answer varies depending upon the weight of the shafts and even the stiffness distributions. So if you are looking a nice tidy frequency or deflection reading for an R-flex 5-iron at x-amount of length it doesn’t exist.

If you are a clubmakers, trying to standardize flex, this is only hindering your fittings and not providing your customers with the right flex. Consumers conducting research on shaft flex can’t look at deflection or frequency readings alone without comparing like weights. Maybe it is time to trust the manufacturers as they have a vested interest in providing product that will fit as there is too much competition to do otherwise.

Consumers are now enjoying the benefits of the new breed of ultra-lightweight steel shafts (2.5g per inch or less). We can thank the manufacturers from deviating from their standard and producing products that fit and feel what they are supposed to be rather than targeting a specific number.